ISSN: 1550-7521

ISSN: 1550-7521

Purdue University Calumet

Visit for more related articles at Global Media Journal

Current television depictions of working women in male-dominated fields represent them from the point of view of the male gaze (Mulvey 1975). This article considers the dangers inherent in audience members’ acceptance and performance of objectifying, stereotypical images of women. The series CSI: Las Vegas will be examined to support this claim.

crime drama, CSI (Crime Scene Investigation), male gaze, women in the media

I have worked in a steel mill in northwest Indiana for ten years. While the mill now employs more women than ever before we are still treated as outsiders in this male-dominated environment. Hence from personal experience I know what it means to be objectified by the male gaze. I am routinely ogled and tested to gauge my reaction to blatantly inappropriate sexual comments. Over the years I’ve cultivated a reputation as a bitch in order to deflect this harassment. But even this label—bitch—does not stop my male co-workers from eyeing me lustily or occasionally inquiring whether I am in a sexual relationship. Indeed, I have been propositioned, asked out on dates by married men, and threatened with physical violence. Decades after the most dynamic years of the twentieth century women’s rights movement, I have no reasonable expectation that my male co-workers will respect me or my privacy. I am the subordinate, sexually degraded Other in the eyes of my fellow workers.

I am not alone. Employed women, especially those who are in leadership positions in fields dominated by men, often are viewed through the parameters of the male gaze. One consequence is that they frequently are subject to negative stereotypes that belittle women’s accomplishments and suggest that successful women use trickery, particularly sexual trickery, to “get to the top.”

The mass media perpetuate these views of women. Indeed, television dramas set in male-dominated workplaces often represent working women, especially those who are authoritative and occupy leadership positions, from the perspective of the male gaze. In this article I will examine such representations of women in CSI (Crime Scene Investigation): Las Vegas.

Mulvey (1975), in her paradigm-setting piece, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” argues that the concept of the male gaze refers to three things: 1) camera position and angles that frame a scene voyeuristically, 2) the actual gaze of male characters when it objectifies female characters and 3) the gaze of the audience when it replicates either the camera’s voyeuristic gaze or male characters’ objectifying gaze.

Mulvey (1989) also asserts that the gaze’s frame of reference is the heterosexual, male experience around which the dominant society is normed. She argues that individual audience members, regardless their sex, view filmed performances through both the camera’s heterosexual, male “eye” and male characters’ perceptions of women. Hence, film and television socialize the audience into the male gaze and in so doing perpetuate hegemonic, patriarchal cultural notions of gender.

For example, in the first five seasons of CSI: Las Vegas, the “number one scripted series in the Nielsen ratings for three years running,” female characters consistently are objectified by the male gaze even as they are shown successfully occupying non-traditional roles for women (“CSI summary,” n.d.). The show’s popularity ensures that this bifurcated but ultimately misogynist representation of women circulates widely. Because the media play a critical role in shaping audiences’ behavior, identity, and values, this representation also informs beliefs about women’s social roles (Carilli, 2005; Del Negro, 2005; Dow, 1992; Heide, 1995; Meyers, 1999; Mulvey, 1975; Signorielli, 1997).

Thursday nights CBS airs CSI: Las Vegas. Dark, gruesome images of bones and body parts burst onto the television screen, which is infused with the solemn faces of the forensic fieldwork team that solve horrific crimes. As it narrates the team’s stories CSI: Las Vegas also portrays the gendered hierarchy that has emerged in the workplace since the mid-twentieth century when the number of middle- and upper-class white women who work outside the home increased substantially.

In 2003, women made up 47% of the total U.S. workforce (McBride-Stetson, 2004, p. 239). However, they held only 19% of the science, engineering and technology posts in the U.S. (Thom, 2001, p. 171). CSI: Las Vegas’ Sara Sidle and Catherine Willows. are fictional members of this 19%. Sara is a single, 30-something loner who sits around listening to a police scanner. Catherine is an ex-stripper and a sometimes single, 40-something mother. Despite their differences Sara and Catherine are both successful forensic scientists. They have resisted patriarchal pressures to opt for careers with higher concentrations of women that are tightly tied to women’s traditional roles as wives and mothers, such as nursing and teaching. Sara and Catherine also exercise a high degree of agency but like the show’s other female characters who exhibit independence and autonomy they do not fare as well as their male counterparts.

Significantly, in CSI: Las Vegas self-determined women frequently are portrayed as fractured if not atomized under the male gaze. Sara and Catherine are among the show’s broken women. Their commitment to forensic science and their jobs is represented in ambivalent terms: Sara and Catherine are depicted as empowered and authoritative but also lacking, which is consistent with patriarchal assessments of women who are successful in nontraditional endeavors. Moreover, Sara and Catherine, because they resist patriarchal norms by performing a “man’s” job, are subject to a persistently invasive voyeurism—the women’s private lives become the focus of public scrutiny—that discourages similar career choices among female audience members.

In comparison to actual crime statistics a disproportionate number of CSI: Las Vegas’ victims are women who, regardless the nature of their work, act with a great deal of agency. But more often than not images of these women are atomized under the scrutiny of the male gaze. This is exemplified in Episode 93, “Viva Las Vegas,” which opens with the image of a bloodied woman lying on a hotel bed (on her back in her underwear). The male suspect is covered in blood but has no memory of murdering the woman:

Officer: She has no ID on her.

Catherine: She has breast implants. (She sees the girl’s transparent Lucite purse and picks it up.) I’m going to guess stripper. She has a locker room key. Could trace it back to the club. How does a guy fall asleep after killing a woman?

Suspect: She must’ve slipped me something.

Catherine: You sure it wasn’t the booze?

Suspect: I never touch mini-bars. That bitch drugged me.

Someone comments that the dead woman has swollen ankles. Catherine replies, “You ever tried shakin’ your ass in four-inch heels?” This hyperattenuated focus on the victim’s ankles is atomizing. It fractures the woman and splits her into disaggregated portions, reducing her to nothing more than a pair of implant-enhanced breasts, a “shakin’ ass” and misshapen ankles. Hence, here as in many other scenes, the female body is fragmented “into eroticized zones such as hair, face, legs, [and] breasts” (Roy, 2005, p. 4).

The male gaze operates similarly with regard to Catherine in Episode 96, “Crow’s Feet.” Catherine and Nick, another CSI, are in a plastic surgeon’s office interviewing the physician about his former patient. The doctor has a camera mounted on his computer. He focuses it on Catherine’s face and zooms in for a close up that reveals every pore and line on her face:

Catherine: Hang on. You consider aging a disease?

Doctor: With a 100 % mortality rate. Aging reeks havoc with every one of our systems: respiratory, cardio-vascular, nervous, muscular-skeletal and the immune.

Catherine: But you’re not treating the body. You’re battling crow’s feet.

Doctor: (Laughs) Righteous indignation. That’s one step before acceptance.

Catherine: Acceptance of what?

Doctor: What I do. The procedures and the products. You’ve seen the ads in all the beauty magazines. You’ve studied all the before and after photos. It’s okay, Miss Willows, we all get older. And nobody wants to look their age. I give you what you need. I give you what you want.

Significantly the doctor addresses Catherine as “Miss” rather than “Ms.” In so doing the surgeon makes an assumption about her marital status and attempts to compliment Catherine by using a salutation traditionally directed toward younger women. The camera angle used in this scene is extremely intrusive. It gives us a view of Catherine that goes beyond ogling and borders on being claustrophobic. Then at the end of the scene a young woman walking down the hall in the doctor’s office contemptuously looks Catherine up and down. Catherine then stops to examine her image in a nearby mirror. She sees herself through the male gaze.

When these texts are juxtaposed they read like patriarchal urban legends. “Don’t stay single”–you will end up dead and naked in a hotel room somewhere. “Don’t age”–no man wants an old, wrinkled, flaccid woman. Notably, the two female victims in these different episodes internalized patriarchal ideals of feminine beauty that are physically and psychologically unhealthy and it killed them both. The victim in “Crow’s Feet” was killed by an anti-aging remedy and the stripper in “Viva Las Vegas” died in the process of capitalizing on patriarchal sexual fantasies about women.

Furthermore, when the camera casts its gaze on the “Viva Las Vegas” stripper’s breasts, ass, and feet it estranges her from her body which in turn socializes female members of the audience into similarly disassociated relationships with their bodies. Overall, in these types of shots women are portrayed as dissembled, objectified body parts rather than integrated subjects with a strong sense of their own personhood. Hence, if taken together, these scenes demonstrate Meyers’ (1999) contention that the “message may be that girls and women can be strong, smart, and independent as long as they remain within the confines of their homes and relationships while also maintaining traditional standards of feminine beauty” (p. 6).

Historically women as a group have had limited access to public power, especially in political and economic spheres. When women finally began to enter these domains they encountered obstacles preventing them from attaining power. Some of the most difficult challenges women must overcome are reactionary representations of female leaders that suggest they are “asexual,” whores, or dominatrixes (Jamieson, 1995, p. 72). These negative stereotypes are deployed with particular intensity in fields where the glass ceiling remains firmly intact and leadership continues to be predominantly male.

Such is the case in most areas of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM). For example, women constitute the majority of students attending higher education institutions but in 2001 only 18.2% were pursuing engineering degrees (McBride Stetson, 2004, p. 157). Likewise, numbers of women enrolling in science and engineering programs are increasing, but women still drop out of them at higher rates than their male classmates while women are significantly underrepresented in STEM (“New formulas,” 2003). As Fara explains, “Until recently, words like physicist, philosopher and mathematician automatically signified a man, so that scientific women were seen as freakish intruders into a male domain.” (Fara, 2004, p. 21). These stereotypes continue to be applied to female STEM practitioners today.

CSI: Las Vegas, a popular, powerful series, could encourage girls and young adults to pursue education and careers in STEM by showing female scientists in a positive light. It occasionally does. For example, in Episode 102, “No Human Involved,” Sara praises a teenage girl, Glynnis, for studying science and encourages Glynnis’ interest in quantum theory:

Sara: You like chemistry?

Glynnis: No. I’m not smart enough.

Sara: Sure you are. Glynnis, right? (Glynnis nods. Sara looks at the cover of her textbook.) Quantum theory. That’s compelling stuff actually.

However, for the most part the show portrays female scientists as either deploying patriarchal values in their relationships with other women, which are strained by animosity and competition, or lacking happy, fulfilling personal lives because of their jobs. Typically, for example, Sara and Catherine look at other female scientists through the lens of the male gaze, condemning rather than supporting female co-workers. Thus, the female scientists of CSI: Las Vegas conform to patriarchal mores just as do many non-fictional women.

This is particularly evident when Catherine is promoted to supervisor. She and Sara become locked in a power struggle as Catherine attempts to assert herself and Sara resists being supervised by a woman. In “What’s Eating Gilbert Grissom?” (Episode 98) Catherine “pulls rank” on Sara after Catherine is promoted to day-shift supervisor. Demanding priority access to lab equipment Catherine asks Sara to hand over a microscope:

Catherine: Sorry, Sara, I need the microscope. Priority.

Sara: I have three more samples to run then I’m finished and it’ll be your turn

Catherine: This can’t wait.

Sara: It can’t or you can’t?

Catherine: Both. Go have a cup of coffee on me.

Sara: (getting up) Coffee’s free.

Catherine: (sitting down) Thank you.

In Episode 105, “Nesting Dolls,” Sara retaliates by attempting to undermine Catherine’s authority. Sara implies that Catherine is an ineffective leader and, in front of the lab’s assistant director, Conrad Ecklie, Sara goes so far as to say that Catherine’s sexuality prevents her from exercising leadership:

Catherine: You know every time we get a case with a hint of violence or domestic abuse, you go off the deep end. What is your problem?

Sara: Yeah. I probably do. And you let your sexuality cloud your judgment about men and I’m gonna go over your head.

In Episode 93 a similar dynamic emerges between Catherine and a newcomer to the lab, Chandra Moore. This episode, “Viva Las Vegas,” opens as Greg is being groomed for fieldwork. Chandra has been hired to replace him. Catherine and Chandra are obviously hostile to each other. For instance, Catherine says to Chandra, “Now, Greg mentioned to you that my stuff gets done first, right?” Chandra replies, “Well, I decide what gets run and when unless Mr. Grissom tells me otherwise.” This rivalry cracks Chandra by the end of this episode. She tells Greg, “I can’t do this. It’s too much for one person. . . . I’m going back to Connecticut.”

In addition to being pitted against each other in the workplace women who enter the public sphere, especially in male-dominated areas such as STEM, often risk having their personal lives exposed to the public. This, writes Jamieson (1995), is a consequence of their violation of patriarchal ideas that 1) women’s proper place is in the home and 2) if women persist in working outside the home they should abandon all their domestic activities including reproduction and childrearing. This latter idea, that women may use either their brains or their wombs but not both, is what Jamieson (1995) refers to as the “brain/womb bind.” According to Jamieson, “Women could use their brains only at the expense of their uteruses; if they did, they risked their essential womanhood. Exercise of the uterus was associated with the private sphere, exercise of the brain with the public” (p. 17).

Women who refuse to be contained by the brain/womb binary and exercise leadership in both public and private spheres frequently are subject to societal voyeurism. Not only are their personal lives exposed in public but the public’s view of women’s private lives is framed by the male gaze. In contrast, men’s personal lives rarely are put on display in this manner.

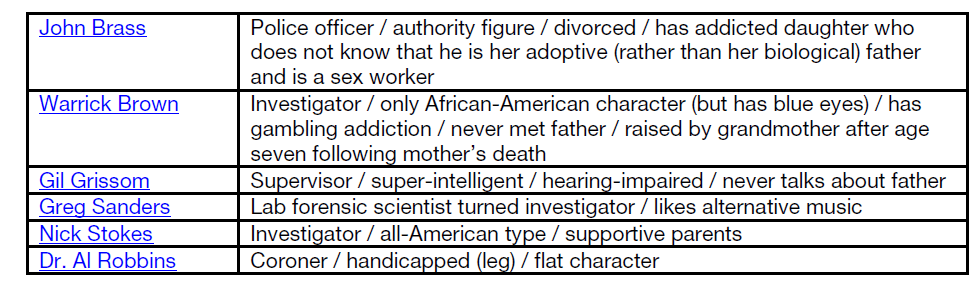

The brain/womb binary as well as the double standard that exempts men from societal voyeurism is conspicuous in CSI: Las Vegas. The chart below demonstrates that the show reveals relatively little personal information about its primary male characters. Interestingly all of these characters are single except for Dr. Al Robbins and Warrick Brown, who married in season six. Conrad Ecklie is excluded from this analysis because he is in few episodes.

Of these men, John Brass’ personal life is most public. Other characters and the audience are aware that his adopted daughter, the product of his ex-wife’s affair, is an addict and sex worker. Significantly, he is portrayed as a martyr for adopting and raising the girl, who does not realize Brass is not her biological father.

Even less personal information is revealed about the other male characters. We do know that Warrick Brown has a gambling addiction but the show emphasizes that he is in recovery and changing his ways. Hence, only two male characters have family-related problems and one of them is depicted as a martyr. Little or no information is provided about the other male characters’ domestic problems

Unlike the male scientists in CSI: Las Vegas the women’s lives often are integrated into the storyline and become the focus of the audience’s and other characters’ voyeuristism. For example, Sara reveals that she has difficult relationships with men in Episode 104, “Snakes,” when she tells Gil that she moved to Las Vegas because of him. She says, “Sometimes I look for validation in inappropriate places.” In the next episode, “Nesting Dolls,” Ecklie tells Gil to fire Sara but instead Gil goes to Sara’s home to question her about a conflict that she had with Catherine. The audience learns about Sara’s adolescent years, her parents, and the effect these experiences and relationships have on her interactions with men:

Sara: I have a problem with authority. I choose men who are emotionally unavailable. I’m self-destructive. All of the above. (She pauses) I crossed the line with Catherine and was insubordinate to Ecklie.

Gil: Why?

Sara: Leave it alone.

Gil: No, Sara.

Sara: What do you want from me?

Gil: I want to know why you’re so angry.

Sara It’s funny – the things that you remember and the things that you don’t. You know. There was a smell of iron in the air. Cast off on the bedroom wall. There was this young cop puking his guts. I don’t remember the woman that took me to foster care. I can’t remember her name, which is strange, you know, ‘cause I couldn’t let go of her hand.

Gil: Well, the mind has its filters.

Sara: I do remember the looks. I became the girl whose father was stabbed to death. Do you think there’s a murder gene?

Gil: I don’t believe that genes are a predictor of violent behavior.

Sara: You wouldn’t know that in my house. The fights. The yelling. The trips to the hospital. I thought it was the way that everybody lived. When my mother killed my father, I found out that it wasn’t (Gil holds her hand as she cries).

This exchange demonstrates that Sara is trapped in the brain/womb bind, for when she tries to pursue both workplace success and an intimate, loving relationship she becomes self-destructive, emotional, insubordinate and unstable.

Catherine’s personal life is also on display in CSI: Las Vegas. Most of her personal problems are related to her role as mother. Catherine, who was raised by a single mother and whose father is a local, mob-tied casino owner, is herself a single mother for most of the show’s episodes. When her daughter, Lindsey, is caught hitchhiking in Episode 95, “Harvest,” the police officer who finds Lindsey questions Catherine’s parenting skills:

Officer: Now, kids this age need a firm hand at home

Catherine: (waves her hand to dismiss him). Thank you (turns to Lindsey). What or who is on Fremont Street that you would risk your life to get to? Mouthing off to teachers, slipping grades and now hitchhiking. I mean, what is next, Lindsey?

Lindsey: Stripping?

Catherine: What did you just say (nervous laugh)? Okay. No phone. No friends. No nothing.

Lindsey: For how long?

Catherine: A month.

Lindsey: (Rolls her eyes) Whatever.

Catherine: Hey. You wanna make it two?

Lindsey: Dad always said you were a drama queen.

Catherine: Well what do you expect, Lindsey, since he was always high?

Lindsey: I’d take dad high over you any day. Nana’s coming to pick me up. I’ll be out front.

Such criticism is a pattern in CSI: Las Vegas. Later in the episode, for example, Catherine shows Lindsey the body of a teenage girl in the morgue. She tells Lindsey a fabricated story that the girl, like Lindsey, believed she could “handle herself.” Lindsey becomes upset when she sees the body on the slab and runs out of the morgue just as the resident coroner, Dr. Al Robbins, enters the room. He passes judgment on Catherine’s parenting abilities:

Al: Kids don’t belong in a coroner’s office unless they’re in a drawer. You should have found a different way to deal with your daughter’s rebellion.

Catherine: With all due respect, doc, this doesn’t concern you.

Al: Ever notice how childhood keeps getting shorter and shorter? Who’s fault is that?

Catherine: I honestly don’t know.

In another episode the mother of a girl who was used to harvest organs for her older brother flings the ultimate insult at Catherine. The mother, who perpetrated the crime against the girl, attacks Catherine’s parenting skills. She asks, “So what kind of mother are you? When do you see her? You work nights. You probably don’t even know where she is half the time. Alicia’s life may not have been simple, but at least I knew her. Can you say the same?” Clearly this scene and others in which Catherine’s parenting skills are criticized suggest that she is unable to manage both a job and her family. These scenes’ common theme is that Catherine’s commitment to her work outside the home prevents her from being a good mother. Catherine, CSI: Las Vegas implies, cannot be both a first-rate scientist and a successful mother.

Catherine’s romantic relationships also are subject to public scrutiny and they tend to show her drawn to men who are abusive or emotionally and psychologically unavailable. However, rather than portraying this as the men’s flaw CSI: Las Vegas faults Catherine. This is evident when the audience meets her low-life ex-husband, a creepy guy she kisses in a bar parking lot in Episode 114 and when Catherine briefly dates a trashy club manager in Episode 93. Neither relationship is healthy and both end disastrously. At the end of Episode 93, for example, the manager breaks Catherine’s heart when she shows up unannounced at his club and catches him having sex with a younger woman. Instead of apologizing or expressing remorse the manager arrogantly defends himself: “What do you expect? I run a nightclub.” Catherine walks out without saying a word. Her silence speaks volumes. It suggests that she has a defeatist attitude and hints that she fears using an empowered voice to “talk back” to disrespectful, abusive male lovers. Therefore, Catherine’s silence signals that she acquiesces to rather than resists the male gaze’s voyeurism.

CSI: Las Vegas’ pattern of making public Sara’s and Catherine’s private lives illustrate the difficulties women encounter when they challenge the patriarchal brain/womb binary. Catherine’s life is put under much tougher scrutiny than Sara’s because Catherine combines a career with women’s traditional role as mother. Sara, on the other hand, is represented as unable to develop healthy, fulfilling relationships with men because she subsumes her needs for emotional intimacy to her scientific work.

CSI: Las Vegas is entertaining and features strong women occupying jobs that they would not have held a generation ago if it were not for feminist social change initiatives. Nevertheless, the show’s female characters struggle with the types of challenges that many non-fictional women face, such as difficult relationships with men, heavy workloads in and outside the home, and raising children as single parents. But CSI: Las Vegas also deploys patriarchal ideologies that limit women by encompassing them within the male gaze. No matter how strong, independent, and successful these women are portrayed they inevitably are objectified by the male gaze, which is dehumanizing:

Objectification does not simply mean that someone is the object or aim of your sexual desire. Rather, it is a systemic process whereby a sentient being is dehumanized, reduced to a thing, a being without social significance or stature, someone turned into something that can be exchanged, bartered, owned, shown off, kept, used, abused, and disposed of. (Caputi, 1999, p. 67)

Such CSI-style, patriarchal representations of women will continue to circulate in the media unless we can craft an alternative schema for narrating women’s life experiences that does not atomize them or put their private lives under the microscope for all to see (Fara 2004). Developing and broadcasting this narrative is a critical step in the feminist project of ending oppression because of television’s influence over how we see the world. In short, new media formulas are required, for what happens in Vegas does not stay in Vegas. It also happens in Northwest Indiana steel mills and innumerable other worksites throughout the world.

Ami Kleminski has worked for U.S. Steel in Gary, Indiana for ten years. During this time she completed her B.A. in Communications at Purdue University Calumet. Currently she is working on my M.A. in Communications focusing on Cultural Studies. Her other academic projects include an autoethnography presentation at the 27th annual conference of the Organization for the Study of Communication, Language and Gender at Saint Mary’s College in Notre Dame, Indiana.

Copyright © 2025 Global Media Journal, All Rights Reserved