ISSN: 1550-7521

ISSN: 1550-7521

Claudia Boyd-Barrett1* and Oliver Boyd-Barrett2*

1Freelance Journalist, Masters candidate, Journalism, Universidad de San Andrésm Buenos Aires, Argentina

2Department of Journalism, School of Media and Communication, Bowling Green State University, Bowling Green, Ohio

Visit for more related articles at Global Media Journal

International 24/7 television news channels have proliferated in the past two decades. Sometimes hailed as a democratization of international television news-space, the perspective of media imperialism theory counsels that this 24/7 trend is more usefully seen as a continuation of a global system of unequal relations in the business and politics of information exchange and diffusion going back at least as far as the establishment of the first international news agencies in the early nineteenth century. The authors assess this perspective in the context of a three-way comparative analysis of coverage by CNN en Español (based in Atlanta), NTN24 (based in Bogota, Colombia) and TeleSur (based in Caracas, Venezuela) during the first days of the aftermath of a coup in Honduras at the end of June 2009, which forcibly removed President Manuel Zelaya from office. The results, largely confirming those of the authors’ earlier analysis of how these channels covered 2009 riots in Iran and Peru, lends support for the application of the terms hegemon, subaltern and counter-hegemon to actors in the domain of 24/7 television news.

24/7 television news; international communication; Latin American media; media imperialism; news agencies; news flow

Analyzing South American international 24/7 television news channels (Boyd-Barrett and Boyd-Barrett, forthcoming) we applied media imperialism theory to a three-way comparative analysis of US-based CNN en Español (CNNEsp), Venezuelan-based TeleSur, and Colombia’s NTN24.

Not all international news media are usefully analyzed with reference to power inequalities among nations, but we believe many of them are ripe for such analysis. Building on overviews of scholarship (Boyd-Barrett, 2006 and Thussu, 2006), we reasoned that international 24/7 television channels, whose market share is dominated by western enterprises such as BBC World and CNN, indicate structural continuities from the global news system initiated by 19th century news agencies Reuters, Havas and Wolff, over one hundred and fifty years ago (Boyd-Barrett, 1980, 1998).

Within that system news agencies could be considered hegemonic, if they were founding members of the original cartel; subaltern, if they submitted to relations of unequal exchange imposed by the cartel on national agencies (e.g. Fabra in Madrid, Spain), or agencies of weaker empires (e.g. Korrespondenz Buro, for the Austrian-Hungarian empire); or counter-hegemonic if resisting the cartel from without (e.g. United Press) or from within (e.g. Associated Press, AP). Two forms of counter-hegemony were indicated: resistance rooted in power struggle among contenders for dominance of a capitalist international economy (e.g. AP); and resistance rooted in anti-capitalist ideologies (e.g. the Soviet TASS, Mao’s Red China News Agency).

This classification mapped on to our three Latin American news channels: CNNEsp as the hegemon, emanating from the center of corporate US power, privileging US news, supporting US foreign policy; NTN24 the subaltern, more focused than CNNEsp on news of Latin America but within a framework of US-style infotainment, and generally favoring US policies; TeleSur the counter-hegemon, ignoring or deprecating US interests. Whereas in the 19th century cartel subaltern agencies depended directly on the hegemons for international news content, in the case of the 24/7 channels, content merely aligned with relations of dependency between the nations that the channels represented. Dependency for actual content might have been determined had we been able to assess to what extent channels adopted directly from western video news agencies APTV or Reuters Television.

The patterns we observed in CNNEsp, NTN24 and TeleSur, reflected the politics of their home governments and inter-governmental relations. US foreign policy tradition regards Latin America as its “backyard,”(Livingstone, 2009) a source of raw materials and profit for US corporations, an area in which intervenes politically and sometimes militarily whenever these interests are threatened by anti-capitalist and/or anti-US governments or movements favoring national and regional autonomy. We would not expect US-based media to demonstrate as much concern as Latin counterparts with Latin American issues beyond the purview of US interests.

The governing regime of Colombia owes its survival, after decades of civil war with guerrilla armies (ELN, FARC etc), to US subsidies, intervention and military encampments, much of this justified by “war on drugs” discourse. We would expect corporate media of Colombia, while more interested than CNNEsp in Latin America, to support US administrations, sharing their pro-corporate, neoliberal Reaganite values. The Administration of Hugo Chavez in Venezuela, by contrast, is suspicious of US administrations which routinely denigrate and subvert it. As a “Bolivarian,” (i.e. advocate for defensive Latin unity against the US) and four-times democratically elected Socialist who supports State subsidy of TeleSur (within a system of mixed public and private media), we would expect TeleSur to manifest perspectives very different from those of US administrations, strongly interested in Latin American issues, sympathetic to the interests of indigenous and other communities oppressed by US or US-supported local regimes.

In our quantitative study of these channels’ main evening broadcasts, supported by case-studies of how they represented 2009 protests in Ecuador and in Iran, we reasoned that coverage would reflect the policies of each channel’s domestic government, and the relations between them. Our predictions were soundly confirmed. For the Honduras case study that follows we examined the evening news broadcasts over a three-day period in July 2009.

Cable News Network (CNN), the world’s first 24/7 television news channel, was founded in 1980 by Atlanta station owner Ted Turner who in 1976 had uploaded WTCG-TV-Channel 17 by satellite, available for downloads by cable operators. CNN in 2009 was owned by Turner Broadcasting Systems, a division of media conglomerate Time Warner. It produces CNN for domestic consumers and CNNI for international. It launched CNNEsp in 1997 as an advertising-supported news service, principally for Latin America, and available in other markets, including the U.S. and Spain. This was the first independently produced CNN 24/7 network not in English language. NTN24 (Nuestra Tele Noticias) was established in 2008 and distributed by DirecTV for Latin America, by cable UNE in Colombia and, additionally, by Telmex and Telefonica. It belongs to RCN Television de Colombia. Originally founded in 1967, RCN was privatized in 1998 under Colombia’s 1995 Television Law, permitting private television channels. In 2008, RCN enjoyed No.2 position on Colombia’s television market, with 29% overall share. It is owned by the Organizacion Ardila Lulle (Colombian media magnate), subscribing to AFP and EFE.

TeleSur was founded 2005, inspired by the success of Al Jazeera (established, 1996). TeleSur is financed principally by the Venezuelan government, but other governments (Argentina, Bolivia, Cuba, Nicaragua, and Uruguay) hold shares. Advocates call it a Pan-American alternative, Latin-style Al Jazeera, providing news from a Latin American perspective. Its Board of Directors supervises the agenda and the Advisory Council includes celebrated Latin intellectuals. Serving an audience of millions spanning five continents, it deploys correspondents in 23 locations in Latin America, New York and Washington, Madrid and London. It broadcasts in Spanish, and in Portuguese for Brazil. After brief excitement in 2005, the channel attracted little further interest from western media or scholars (but see Paynter, 2006). Both TeleSur and NTN24 promote themselves as alternatives to CNN and western news media. Their slogans emphasize Latin American collaboration: NTN24’s “Our” Tele Noticias, and TeleSur’s “Our North is the South”. They claim they fill a void, with news they say foreign media ignore or poorly interpret.

We expected that the 2009 Honduras coup would ideologically divide international 24/7 channels. To viewers for whom news from Honduras was a relative novelty, here was the forcible removal of a democratically elected president by a cabal representing bourgeois, military, and neo-liberal interests. Mixed signals from Washington (despite its official condemnation of the coup) created confusion as to whether or not the US was covertly involved, as a right-wing shift in Honduras would likely favor US interests. If so, this might signal a returning point - within weeks of the announcement of new US military bases in Colombia (some feared they might be used against Venezuela) - to the days of covert US operations against Latin American governments or movements that the US considered insufficiently reliable. CNNEsp, we surmised, would adopt a posture of “balance” between opponents, treating each party as equals, thus whitewashing criminal overthrow of a legitimate state. TeleSur would vehemently oppose the plotters, while NTN24 coverage would be closer in tone to CNNEsp than to TeleSur.

A crisis foretold

Even before president Manuel Zelaya was roused at gunpoint on June 28th, 2009, and bundled by plane to Costa Rica, big trouble was clearly brewing in Honduras. Zelaya was progressing plans for a non-binding referendum that had roused rabid opposition from conservative politicians and military. The referendum was on whether to allow Hondurans to vote during November’s national elections on a constitutional amendment permitting presidents to seek reelection (Mejia, 2009). Critics saw it as an attempt to hold on to power. The referendum was scheduled for Sunday, June 28th, the same day Zelaya was ousted.

Throughout the preceding week, political tensions were at boiling point. On Tuesday, June 23rd, the Congress passed a bill rendering the upcoming referendum illegal. When chief of the armed forces, Gen Romeo Vasquez, said he therefore could not help organize the referendum, Zelaya fired him. Other military leaders resigned in protest. The Supreme Court ordered Zelaya to reinstate Gen. Vasquez, but Zelaya refused. On Thursday June 25, with supporters, Zelaya entered a military base to seize ballot boxes being stored there. The military deployed hundreds of troops to the capital, Tegucigalpa, in a bid to prevent disturbances by Zelaya supporters (BBC 2009).

These events went unnoticed by most mainstream U.S. media, including CNNEsp. There was little reference to these events leading up to the coup. From June 25 any news from Honduras (or from petty much anywhere) was overshadowed on CNNEsp by round-the-clock coverage of the death of celebrity Michael Jackson. So when the coup happened, June 28, it appeared on CNNEsp as out of the blue.

Not so on TeleSur. For days before the coup, the Honduran crisis and Zelaya’s defiance of Congress and Supreme Court featured prominently. When Zelaya and his supporters wrestled ballot boxes from military storage, TeleSur featured a speech by Venezuelan President Chavez about the crisis, in lieu of its regular newscast. Watching TeleSur, it seemed certain that something dramatic was underway.

Our analysis looks at coverage on July 1st, 2nd, and 3rd, shortly after the coup. We were unable to obtain complete recordings of the three channels’ broadcasts prior to those dates, particularly of NTN24, and those dates fell outside of the research plan. From what could be observed prior to the coup, CNNEsp’s apparent lack of interest in Honduras versus TeleSur’s breathless coverage of each new development, was notable. This reveals TeleSur with its nose to the regional ground contrasting with CNNEsp’s narrow, U.S.-focused news agenda.

Yet, TeleSur’s eagle-eyed coverage prior to the coup underlines the channel’s deference to Venezuelan political priorities. Zelaya was close to Chavez, a friendship that worried Zelaya’s enemies. Under Zelaya, Honduras joined Chavez’s Bolivarian Alliance for the Americas (ALBA) and Chavez reportedly flew ballot materials to Honduras for the referendum. Following June 28, Chavez condemned the coup, even threatening military intervention (Daniel and Pretel, 2009; Weissert and Cuevas, 2009). He lent Zelaya an airplane for travel throughout Latin America and to the UN to rally foreign leaders (Bridges, 2009).

In the Wake of the Coup

The days following the coup in Honduras were tumultuous, while the world and many Hondurans were trying to establish what was really happening. Access to credible media was all-but blocked inside Honduras. Many international outlets, including CNNEsp and NTN24, appeared caught off guard, unsure how to make sense of the crisis.

We examined CNNEsp, TeleSur and NTN24 newscasts from July 1st to July 3rd. There are significant differences in how each channel covered news on these days. But before examining these, it is useful to overview events as corroborated by a wide range of reports.

Honduran President Manuel Zelaya was seized by military officers and forcibly exiled on June 28, 2009, the same day the controversial referendum was to be held. This was the first military coup in Central America since the cold war. On Sunday, lawmakers appointed veteran congressional leader Roberto Micheletti as interim president. The interim government ordered a nationwide curfew starting at 9 p.m. Electricity went out in Tegucigalpa and broadcast stations went off the air. Military patrolled the streets and guarded government buildings. Immediately, several thousand protesters expressed support for Zelaya outside the presidential palace (Malkin, 2009). Protests continued Monday, with thousands of Zelaya backers facing soldiers who fired tear gas on protesters after these blocked streets, set fires and hurled stones (Cooper and Lacey, 2009).

Military arrested journalists, including some AP and TeleSur reporters, although these were released shortly (Associated Press, 2009). Soldiers closed pro-Zelaya media outlets, including Channel 8, official government broadcaster. By Tuesday, a new band of protesters arrived on the streets of Tegucigalpa, to express support for the interim government and denounce Zelaya (Lacey, 2009). The pattern of two-sided protests continued, mainly in Tegucigalpa and the second-largest city, San Pedro Sula. Military repression against pro-Zelaya factions also continued, along with pervasive censorship. Heavy-handed tactics of the coup regime were documented by NGOs, including Amnesty International and the Inter American Press Association (Amnesty International, 2009a, 2009b). The international community sided with Zelaya, condemning the coup as illegal. These included the UN General Assembly and the USA (Feller, 2009)(1) Various countries withdrew ambassadors, and Honduras’ neighbors - Guatemala, El Salvador and Nicaragua – announced they would halt commerce with Honduras (Malkin, 2009).

On Wednesday July 1, the Organization of American States (OAS) issued a 72-hour ultimatum threatening to suspend Honduras if it did not restore Zelaya. Zelaya had talked of returning the next day, but now said he would postpone his return until the 72-hours were up. The U.S. suspended military cooperation with Honduras, while Spain, France, Italy, Chile and Colombia began recalling their ambassadors. In Honduras, Congress issued an emergency decree extending the curfew, giving authorities the power to arrest people in their homes, and restricting public gatherings (Booth and Sheridan, 2009).

On Thursday, after lengthy debate, the OAS announced Jose Miguel Insulza would travel to Honduras the next day to demand Zelaya’s return to power. Insulza arrived in Honduras Friday, July 3, and met with political and judicial leaders but not Micheletti. His visit proved unsuccessful. The Guatemalan Nobel laureate Rigoberta Menchu also arrived (at the request of Micheletti) to help mediate (Associated Press, 2009) (2).

Covering the coup

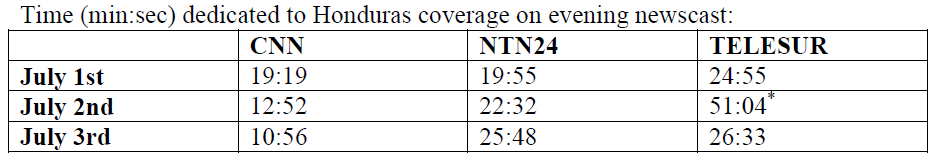

The coup was major news throughout Latin America and worldwide. Honduras was the top headline on all three channels on the days studied. Each channel also dedicated extensive air time to the crisis:

TeleSur provided the most coverage, followed closely by NTN24. Heavy coverage remained steady on those channels throughout the three days, while CNNEsp’s attention shrunk steadily. TeleSur, hyper-attentive to events even before the coup, remained consumed with it. Honduras dominated all news coverage – taking up the entire evening newscast on July 2 - and promos of TeleSur footage of the crisis were replayed even during commercial breaks. Consequently, the channel incorporated a greater variety of news elements related to the crisis than its rivals (see Tables 4b through 4d).

Honduras offered a perfect opportunity for TeleSur to gain exposure as a robust, alternative, on-the-ground voice in Latin America’s mediascape. With ample journalistic resource and airtime focused on Honduras, TeleSur provided live, up-to-the-minute coverage that other channels could not match. TeleSur obtained numerous scoops, including the first interview with Zelaya after his ouster and live footage of his attempted return to Honduras, July 5. At times, TeleSur was the only channel with a live feed of the pro-Zelaya protests (Daniel, 2009). During the three days, TeleSur showed footage and interviews from the widest variety of locations, both in Honduras and throughout the Americas, as it followed international reactions to and diplomatic efforts to restore Zelaya.

TeleSur’s dedicated focus on the coup’s detractors earned it hero status among Zelaya supporters. The breadth and immediacy of TeleSur’s coverage earned it respect from other media. CNNEsp rebroadcast TeleSur video, although not during the newscasts we studied. Western news outlets – including Bloomberg, Reuters and the BBC - cited TeleSur information and interviews.

A tale of two protest movements

Each channel covered the same essential details of diplomatic efforts to restore Zelaya, as well as pronouncements by Zelaya and the coup leaders. In reports on the protests, however, TeleSur’s coverage differed sharply from CNNEsp and NTN24.

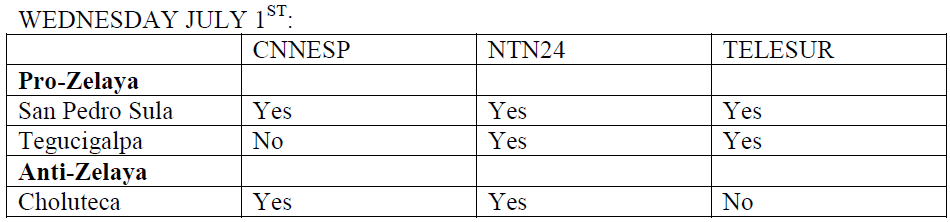

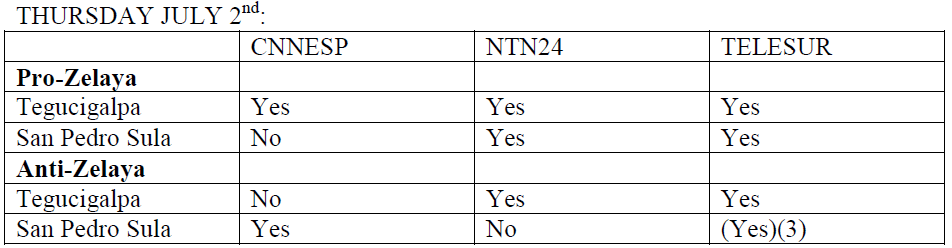

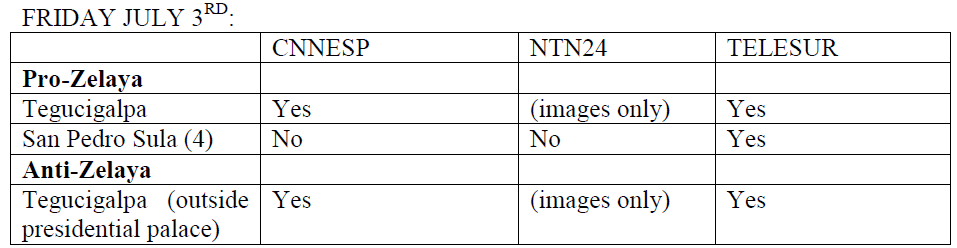

Identifying which side was protesting where, July 1-3, was difficult to determine from the selected newscasts alone. At times the news on one channel appears to contradict the other. For example, on July 2nd CNNEsp broadcast a report about pro-Zelaya protests in Tegucigalpa and pro-coup demonstrations in San Pedro Sula, the nation’s second largest city. NTN24 and TeleSur aired reports about pro and anti- Zelaya protests in Tegucigalpa and in San Pedro Sula but, except for a very brief mention on TeleSur, did not talk about pro-coup protests in San Pedro Sula.

There were pro and anti-coup demonstrations each day across the country. Below is a brief summary of where the main protests were as confirmed by various news sources, and which of these protests were covered by each channel.

As shown, all three channels reported protests for and against Zelaya. The exception was TeleSur on July 1, which did not mention anti-Zelaya marches. NTN24 only showed images of each side protesting on Friday July 3rd. But there were significant differences in how the channels presented their reports on the protests.

TeleSur mentioned anti-Zelaya protests, but overwhelmingly focused on Zelaya’s supporters. TeleSur started and concluded newscasts with several seconds of images of pro-Zelaya protests. It repeatedly returned to images of pro-Zelaya protests throughout the newscast. During commercial breaks it ran promos about its Honduras coverage, including pro-Zelaya protest images. All but one of TeleSur’s street interviews was with Zelaya supporters. The exception was a man at a pro-Micheletti rally, but his comments favored neither side.

TeleSur was the only channel that considered people travelling from around the country to Tegucigalpa to express support for Zelaya, featuring interviews with people who had walked long distances and who testified to military intimidation on route. This concurred with other news outlets and NGO reports. Particularly noteworthy was the station’s reports on intimidation of Zelaya supporters by security officials and government, including emotional testimony from protesters who denounced military and police violence, and images of heavily armed and shielded military and police watching the protesters. The most dramatic images, from San Pedro Sula. TeleSur on July 2, showed police firing guns (one could not see who they were firing at), tear gas and arresting people. July 1 footage showed a group of soldiers appearing to converge on a man, beat and detain him. Some footage did not clearly corroborate the newscaster’s description. On July 2 the newscaster introduced images he said showed police repression. What they appeared to show were pro-Zelaya protesters burning tires in the street.

Repression of Zelaya supporters was well documented by credible sources. Amnesty International reported wide-ranging human rights abuses, including: “killings following excessive use of force, arbitrary arrests of demonstrators by police and military, indiscriminate and unnecessary use of tear gas, ill treatment of detainees in custody, violence against women, harassment of activists, journalists, lawyers and judges”(Amnesty International, 2009). On July 5, soldiers opened fire on protesters trying to access the airport where Zelaya was attempting to land. At least one was killed and eight others wounded (Lacey and Thompson, 2009).

TeleSur reported other types of repression and intimidation such as electricity blackouts and alleged forced military recruitment (5). It tackled media censorship which kept residents ill informed as to what was occurring – also well-documented (Forero, 2009). Restrictions imposed on civilians by the coup government featured heavily in TeleSur reports. Congress issued on emergency decree on July 1, extending an overnight curfew, banning gatherings of more than 20 people, limiting freedom of movement and speech, giving authorities the power to arrest people in their homes and hold them for more than 24 hours. TeleSur announced this in its headlines and included a 90 second telephone interview about the decree with a congresswoman who opposed the restrictions.

TeleSur ignored anti-Zelaya rallies or only mentioned them in passing without images or interviews. On July 2, the reporter referenced marches in favor and against Zelaya in San Pedro Sula, but all subsequent coverage concerned pro-Zelaya marches. The reporter emphasized that only Zelaya’s supporters were repressed by police. TeleSur did report a major anti-Zelaya rally on Friday, July 3 before the palace, addressed by Micheletti, on the same day of the OAS general secretary’s visit (in which the secretary snubbed Micheletti). TeleSur questioned the rally’s legitimacy. It focused on rumors that government employees and workers at private companies had been forced to attend or lose their jobs. Such allegations, difficult to prove, were not unique to TeleSur. Honduran activist Bertha Oliva, speaking on the Real News Network (Freeston, 2009), also said she believed people were forced to attend pro-Micheletti rallies. She indicated the power of Honduran media to censor debate and sway public opinion. According to the Inter Press Service (IPS), the vast majority of broadcast stations and print publications in Honduras are owned by six families (Mejia, 2008).

None the less, it is hard to believe that all the thousands of people attending pro-Micheletti rallies did so against their will or out of misinformation. Zelaya was supported by some social sectors, certainly, but overall was not a particularly popular president. A Gallup poll conducted two days after his ouster showed that 41 percent of the population agreed with his removal, including a majority of residents in Tegucigalpa and San Pedro Sula (CID-Gallup, 2009). (46 percent of Hondurans disagreed with his removal).

CNNEsp and NTN24 coverage reflected this notion of a divided country. Whenever dealing with the protests they gave each side approximately equal weight. The newscaster’s introduction was typically “today protests continued in favor and against the new government” or, for example on CNNEsp: “This story has two sides, and now we show you the other.” NTN24 refers to Honduras as “a fragmented country”. If anything, CNNEsp emphasized anti-Zelaya protests. On all but one occasion, CNNEsp mentioned anti-Zelaya rallies first. This may be partly due to syntax: it is common to say “for and against” in that order. However, this plays out in other ways, with footage of the pro-Micheletti protests generally broadcast first. NTN24 was more even-handed in this respect.

There were glaring omissions on both channels. Neither dealt directly with police repression or media censorship (in the period studied). The only exception was on July 2, when NTN24 briefly mentioned that police threw tear gas at protesters in San Pedro Sula. The channels did not show images of this or any other type of repression. They did not address reports or allegations about media censorship, forced military recruitment, arbitrary detentions, electricity blackouts or people blackmailed into attending pro-Micheletti rallies. CNNEsp host Daniel Viotto did read emails from people in Honduras, some of them mentioning repression and censorship. These were read alongside emails criticizing Zelaya and his supporters. NTN24 reported pro-Micheletti demonstrators paying tribute to the Honduran military and thanking them for their service, on July 1. The channel reported alleged violence and vandalism by Zelaya supporters, including a grenade thrown at the Supreme Court building, June 30 (6). The reporter cited these incidents as the reason for the government-imposed curfew, an ingenuous interpretation.

On July 2, CNNEsp showed soldiers with guns patrolling the streets but accompanied these with images of people burning tires and a man waving a machete. Reports of violence and vandalism by pro-Zelaya demonstrators surfaced in other media articles. A report by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights confirmed some serious acts of violence and vandalism by protesters, while noting that the majority of demonstrations were peaceful, and finding that widespread human rights violations by authorities was a much greater problem (7).

TeleSur did not report directly on protestor violence or vandalism. It showed angry protesters burning tires and newspapers, within a discourse about angry populace demanding justice. For example on July 2, the newscaster introduced images that included tire-burning as follows: “These images collect and reflect the popular dissatisfaction in Honduras.” CNNEsp and NTN24 ignored the coup government’s emergency decree and curfew. NTN24 only mentioned the curfew on July 1 in context of it being a response to violence by Zelaya supporters. The channel did not mention other infringements on civil liberties imposed by the decree. The only mention of these by CNNEsp was on July 2, when the host said people protested in Tegucigalpa “against the suspension of some individual guarantees during the hours in which the curfew is in effect.” Nothing else was said regarding this issue throughout the entire three days.

The absence of solid information about repression, censorship and infringement of civil liberties on both channels is alarming, particularly given CNNEsp’s repeated insistence that it was covering “all angles”. These incidents had been documented by other sources, and TeleSur’s own cameras bore witness to some of them. It could be argued that NTN24 and CNNEsp did not reference these issues because they did not have evidence. However, the channels happily repeated allegations by the Micheletti government and its supporters that Venezuelan president Hugo Chavez was interfering in Honduran affairs (see below). This also was difficult to prove (8).

CNNEsp’s and NTN24’s portrayal of protest movements as two equal sides with a different point of view was simplistic and misleading. While appearing as journalistic objectivity, the strategy distorts an uneven power struggle. Pro-Zelaya protesters, many from impoverished areas, were risking their lives to defy the coup government’s repressive tactics and resist an undemocratic overthrow of an elected leader. Meanwhile, the pro-Micheletti demonstrators – most probably fed a steady diet of anti-Zelaya propaganda from the Honduran media - enjoyed the benefits of military protection and the approval of the usurping powers. By giving pro-Micheletti demonstrators equal credence and omitting information about oppression and censorship of Zelaya supporters, the channels diluted the violent and illegal nature of Zelaya’s ouster and played into the hands of the coup government.

CNNEsp’s and NTN24’s approach to the protests was bland and superficial coverage. It was also questionable journalism (9).

The San Pedro Sula question

Zelaya was not the only Honduran leader forced out of office. Many of his allies were detained and threatened, including the mayor of San Pedro Sula – Rodolfo Padilla Sunseri- who was obliged to leave the country (Malkin, 2009).

The details of Padilla’s departure are murky – an archival search failed to locate details of exactly what happened to him – but clearly his sudden and suspicious departure was a flashpoint of controversy in his hometown during the first days of July. TeleSur was the only channel to report on Padilla’s ouster and to broadcast statements about it from outraged protesters in San Pedro Sula. It contextualizes the large demonstrations held in that city on July 2. TeleSur also reported that authorities attempted to replace Padilla with a nephew of Roberto Micheletti. This has been impossible to corroborate, but it is clear from local newspaper reports that by July 3 vice-mayor Eduardo Bueso – not the nephew - had taken charge (La Tribuna, 2009).

The Chavez question

Zelaya’s opponents accused the deposed president of colluding with Venezuelan president Hugo Chavez to form a populist dictatorship. This was one of the coup leaders’ central arguments for deposing Zelaya, picked up and recited repeatedly by international media. Zelaya did move increasingly to the left during his tenure, rallying against the country’s elite, gaining support of labor unions and the poor, and aligning himself with Chavez. But as Mark Weisbrot, co-director of the Washington-based Centre for Economic and Policy Research points out, Zelaya’s relationship with Chavez was unremarkable. Zelaya was nowhere near as close to Chávez as any number of other less controversial Latin American presidents, including those of Brazil and Argentina (Weisbot, 2009). Zelaya’s quest for a possible second term in office was not an exclusively Chavez-inspired or left-wing phenomenon. Presidents across Latin America have sought to expand their term limits in recent years, with varying success - including Colombia’s U.S.-aligned Alvaro Uribe (Olson, 2009).

Chavez was a forceful critic of the Honduran coup. Immediately following Zelaya’s ouster, Chavez threatened to do everything he could to restore Zelaya, saying he would “act militarily” if troops dared to enter the Venezuelan embassy in Honduras (Usborn, 2009). To date Chavez has not taken any such military action and has vehemently denied accusations of interference. Meanwhile, his words have been all but overshadowed by the larger international outcry over the subversion of democracy in Honduras.

For the coup authorities, Chavez was enemy number one. Following the coup, Roberto Micheletti even said he would welcome Zelaya back as a private citizen if he stopped supporting Chavez (Weissert, 2009). The new authorities framed their coup as a kind of anti-Chavez resistance movement. They accused Chavez of inciting the anti-coup protests and of interfering in the country’s affairs (Weissert, 2009).Honduras’ coup-aligned media bolstered the hysteria with reports that “foreigners” – Venezuelans, Nicaraguans, Ecuadorians and Cubans – had been discovered organizing and participating in pro-Zelaya protests (10). The paranoia was such that Edgardo Dumas, publisher of La Tribuna and the country's former Defense Minister, accused CNN of being "on the payroll of the dictator of Venezuela Hugo Chavez” (Benjamin, 2009).This theme was heard at pro-Micheletti demonstrations. Footage shows protesters chanting anti-Chavez slogans and waving signs denouncing Venezuelan interference.

Determining the truth of such accusations is beyond the scope of this research. It was also apparently beyond the scope of most international media outlets, who generally reported the coup government’s anti-Chavez concerns without verifying the claims with outside evidence. Both CNN and NTN24 gave substantial prominence to rumors about Chavez-led interference, although CNN was the more cautious.

On July 2, CNN reported anti-Zelaya protests in San Pedro Sula where demonstrators denounced “what they consider to be” interference from Chavez in Honduran affairs. Later in the report, the correspondent said Chavez had become a central flashpoint in the conflict. He backed this up with interviews with ordinary citizens who said they were fearful of Chavez’ influence. Footage on July 3rd shows anti-Zelaya demonstrators holding up signs connecting Zelaya with Chavez, Cuban leader Fidel Castro and Bolivian president Evo Morales.

NTN24 emphasized Chavez’ reaction to and his alleged role in the conflict. The channel reported on Chavez threatening to cut oil to Honduras, hinting that he might use military force to topple the coup government (although in the clip NTN24 provided, Chavez did not actually say this). During a live conversation with the correspondent in Tegucigalpa on July 1st, the NTN24 newscaster asked the following less-than-subtle question:

“Are there any indications in the local press that there are people from Nicaragua and Venezuela infiltrating and inciting these protests?”

To which the correspondent answered “yes”, adding that Cubans had also been detected “according to police”.

The channel also featured two “independent” news items to reinforce the “Chavez interference” narrative. One was an interview with Venezuelan opposition leader Manuel Rosales, who blamed the crisis on a “monster” (i.e. Chavez) who had extended himself across the continent. The second dealt with an editorial in the conservative Wall Street Journal that essentially applauded the coup instigators for rescuing Honduras from Chavez’ unsavory influence.

It seems reasonable, given the prominence of anti-Chavez rhetoric in the Honduran conflict, that CNN and NTN24 should have given the issue some attention. Nevertheless, NTN24’s uncritical focus on anti-Chavez opinion-makers leaned away from objective journalism. It was unfortunate that both channels chose to give weight to Honduran fears about encroaching “Chavismo”, but virtually ignored equally important concerns about military repression and media censorship.

TeleSur, on the other hand, failed to even mention the Chavez controversy. The only allusion was in a speech broadcast in which Chavez denied intervening in Honduras. TeleSur interrupted its regular news program on July 2 to broadcast live almost 20 minutes of this speech. By failing to address the accusations against Chavez head on, TeleSur once again demonstrated the ideological constraints on its ability to report news from all angles. By giving 20 minutes of iprogram time to a rambling speech by Chavez, the network damaged its claim to be a politically independent news source.

All hail the Wall Street Journal

The Wall Street Journal published an editorial following the coup justifying Zelaya’s ouster as necessary to defend democracy. The paper criticized Zelaya’s planned referendum and his alliance with Chavez, and repeatedly chastised him for being “leftist.” The Journal swiped at the government of U.S. president Barack Obama for speaking out against the coup, and referred to “tens of thousands” of pro-coup demonstrators without mentioning those protesting for the return of Zelaya (O’Grady, 2009).

Both CNNEsp and NTN24 seized on this editorial. NTN24 dedicated a segment of its evening newscast to it, while CNNEsp assembled a separate news program to discuss the editorial. Why did these channels deem the Wall Street Journal’s opinion to be of such overriding significance? There were many other editorials to choose from that would have offered a very different opinion. Honing in on the opinion of one U.S.-based newspaper betrayed an imperialistic take on Latin American affairs – flying in the face of NTN24’s claims to be the channel “by Latinos and for Latinos”. More relevantly, the Wall Street Journal is owned by ultra-conservative media mogul Rupert Murdoch and is hardly an objective source of opinion. To give such prominence to views expressed by this paper was a highly questionable decision.

Coup-sponsored charges

Shortly after the coup, the interim authorities issued 18 charges against Zelaya, including treason and abuse of authority, threatening to arrest him if he returned (Lacey, 2009). The Micheletti government defended Zelaya’s ouster, saying it was not a coup. All three channels covered the charges, but their approaches differed.

NTN24 reported on the charges against Zelaya on all three days, on one occasion giving details on each charge. On July 2, the network featured an extensive interview with the president of the Honduran Supreme Court Jorge Rivera Aviles in which he justified the government’s actions. On Friday July 3, NTN24 reported claims by the coup government that it had suspended Zelaya’s credit cards, allegedly used for expensive clothes and hotel stays. This last report might have been true, but its source was suspect. The government obviously released the information to discredit the ousted president. NTN24 should have been more skeptical (11).

CNNEsp reported more briefly on the coup government’s charges against Zelaya, and provided greater balance. On July 2, CNN reported on a statement by the Honduran prosecutor that he had enough evidence to try Zelaya for treason and abuse of authority. The newscaster followed this up with Zelaya’s response that the coup authorities should have allowed him to stand trial instead of forcing him to leave the country.

TeleSur reported on the coup government’s charges, but followed up with a counter-attack. The channel initially mentioned the charges July 2. The next day, it gave a minute-long bullet-point presentation of Micheletti’s political career and numerous incidents in which Micheletti allegedly violated the Honduran constitution himself.

A variety of viewpoints?

TeleSur far outstripped CNN and NTN24 in the quantity of people it interviewed. For example, on July 1, TeleSur offered soundbites from 19 people, compared with six on CNNEsp. NTN24 featureed only seven soundbites, all from officials.

The array of voices heard on TeleSur was broader and more imaginative than on the other channels. In addition to the sound bites from the conflict’s key players – Manuel Zelaya, Roberto Micheletti – and other officials, TeleSur reporters interviewed protesters, union leaders, farm workers and human rights defenders.

This effort to evoke voices of the underdog was commendable. However, the variety of voices did not extend to opinions expressed. Virtually everyone interviewed by TeleSur supported Zelaya and/or condemned the coup. The network even interviewed random, lesser-known officials, such as an ex mayoral candidate for Tegucigalpa, for no apparent reason other than that they were against the coup. When TeleSur reporters did interview someone at a pro-Micheletti march, the selected sound bite was apolitical and did not endorse either side.

TeleSur broadcast daily sound bites from Venezuelan officials critical of the coup. These included Venezuela’s foreign minister, the interior minister, Hugo Chavez and the President of Venezuela’s National Electoral Council.

Both CNNEsp and NTN24 presented a wider variety of opinion on the coup that TeleSur, even though they interviewed fewer people. These included protesters for and against Zelaya, coup authorities and international diplomats involved in the crisis. The channels spent less time than TeleSur covering events on the street, focusing mainly on the official realm.

CNNEsp excelled in offering views and analysis from people not directly involved. The CNNEsp correspondent travelled to smaller towns in Honduras which were not the scene of protests – Zelaya’s hometown of Catacamas and Micheletti’s hometown of Progreso – and interviewed people there. This was a novel attempt to provide a sense of how things looked for regular people on the ground. However, the interviews were generally less than satisfactory because the subjects seemed mostly clueless as to what was going on.

CNNEsp’s “Encuentro” was the only newscast to interview outside analysts. These included an International Law professor at Columbia University, and analysts from the Carter Center and the conservative Hudson Institute. That all of them were based in North America was indicative of CNNEsp’s U.S.-centric mindset, but it was a sensible strategy to go beyond the partisan fray in and seeking a more detached understanding of events. Neither TeleSur nor NTN24 attempted to do this.

CNNEsp also incorporated the opinion of regular Honduran people through reading viewer emails on the air. These emails were selected so as to give exposure to arguments both for and against the coup. TeleSur broadcast letters from Honduran viewers on July 2nd, but these letters served a self-congratulatory purpose, praising TeleSur for its coverage.

International perspectives

There were some differences in how each channel covered international reaction, with NTN24 and TeleSur in particular offering a broader perspective than CNNEsp, which was much more U.S.-centric.

CNNEsp focused on pronouncements by the USA and the OAS (of which the USA is a member). In contrast, TeleSur incorporated the reactions of individual countries throughout Latin America, those of countries neighboring Honduras and statements from pro-Zelaya officials who remained in Honduras. In so doing, TeleSur presented a picture of a much greater groundswell of international support for Zelaya than did CNNEsp. Both NTN24 and TeleSur included the reactions of European countries, and the support given to Zelaya by the presidents of Nicaragua, Argentina and Ecuador, who offered to accompany the deposed president on his return to Honduras. Both channels featured interviews with Guatemalan Nobel laureate Rigoberta Menchu about her visit to Honduras July 3rd.

Language lessons

Newscaster use of language to describe the coup and its various players was revealing. All three channels called what happened in Honduras a coup, but they used different terms for referring to Micheletti and Zelaya.

On CNNEsp, newscaster Daniel Viotto used the terms “President Roberto Micheletti”, “the Micheletti government” and “the current government”. He calls Zelaya “the deposed Honduran president”. NTN24 started off uncertainly, but used more definite terms as the days progressed. It began calling the crisis a coup, but later called it “the institutional crisis”. During the first two days, the newscasters refer to Micheletti as “the head of state designated by the congress”, and to his government as “the current government” and “the interim government”. By July 3 the newscasters call Micheletti “the new Honduran leader” and his government “the new administration.” TeleSur’s language was more accusatory: The channel referred to Micheletti as “the illegitimate president”, “the de facto president” and “the usurping president”. When talking about Zelaya, TeleSur newscasters and reporters called him “the legitimate president” and “the constitutional president”. The news presenters also made reference to the Honduran army as “the coup forces”.

Each channel chose to include and omit certain information and voices, emphasize particular issues over others and use different language to describe the actors involved. TeleSur focused on pro-Zelaya factions and abuses by the usurping powers, while CNNEsp and NTN24 provided a superficially balanced view of events that failed to dig into important issues of repression and censorship and arguably lent too much credence to the coup regime.

Here is a summary of the storyline that emerged from each channel:

According to CNNEsp, Honduras was divided down the middle. Some people supported Zelaya and an equal number of people did not like him. There were protests involving thousands, but repression and media censorship were not problems worth mentioning. A lot of people believed Chavez was stirring up trouble.

NTN24 also presented the Honduran conflict as a disagreement between two equal sides, and skirted around the issue of police repression. Through daily and detailed repetition of the coup government’s charges against Zelaya, NTN24 pushed the idea that Zelaya did something bad and that was why authorities got rid of him. The channel emphasized allegations that Chavez was to blame for the crisis.

The story on TeleSur was one of massive chaos and repression. The channel began each day’s news coverage with images of pro-Zelaya protests swarming through the streets and facing off against violent security forces. By focusing almost exclusively on the people who supported Zelaya, TeleSur gave the impression that virtually everyone in Honduras favored the deposed president’s return. Those who participated in the anti-Zelaya demonstrations are dismissed as people who had been paid or forced to attend.

TeleSur’s one-sided approach fitted with the pattern identified in coverage we previously monitored in its coverage of Iran and Peru. The channel aligned itself with the views of Venezuela’s leaders, even interrupting its regular newscast to bring in live footage of a speech about Honduras by Hugo Chavez. Nevertheless, because TeleSur’s perspective on this occasion gelled with international sentiment about the coup, its overt bias appeared less egregious. By focusing on the plight of pro-Zelaya protesters the channel became an emotive voice for thousands of Hondurans who were otherwise drowned out by in-country censorship and superficial reports from other news channels.

CNNEsp’s approach to the conflict was bland and one-dimensional. By failing to mention repression by the coup regime, and ignoring issues such as the ouster of the mayor of San Pedro Sula, the channel provided a falsely benign interpretation of events.

NTN24 was similar to CNNEsp, although appeared to err more decisively on the side of the Honduran elite. The channel uncritically rehashed information from suspicious sources: the coup government itself and the Honduran media.

No channel emerged critically unscathed. TeleSur projected an unmistakable bias, while CNNEsp and NTN24 muddied chances for genuine understanding by omitting information and shying away from in-depth or critical reporting. Of TeleSur we can say that it was paying attention well before the coup, and mobilized smartly to cover events with generous resources and airtime, while its rivals appeared caught off guard and insufficiently cognizant of regional implications. TeleSur’s prioritization underscored its appreciation of implications for the entire continent, even while it unmistakably sided with Zelaya and his supporters. TeleSur paid more attention to ordinary people, and to a broader swath of issues as these affected different parts of the country, even if the ordinary people it mostly represented were pro-Zelaya supporters (arguably the most egregiously wronged). It testified to the diversity of manifest abuses (chronicled by NGO sources such as the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights). In doing so, it sided with the poor, oppressed and indigenous.

CNNEsp and NTN24 were superficially more “balanced” between contending factions but this was belied by language that accorded Michelletti legitimate status as president. Neither station cared sufficiently either for the constitutional implications or for the victims of repression. By exaggerating the bogeyman of interference in Honduran affairs by Venezuela’s President Hugo Chavez, they leveraged events to support a US campaign of denigration against a democratically-elected leader who had resisted US intervention in Latin America. In this respect, NTN24 was even more shrill than CNNEsp, perhaps reflecting Colombia’s greater nervousness about Venezuelan power. CNNEsp did approach external experts, although these were all US-based; CNNEsp’s sources for international reaction also tended to be US-centered, unlike those of TeleSur which represented a range of Latin American voices.

The case study raises ethical questions about uncritical adoption of and support for classic Anglo-American approaches to journalism, suggesting that the appearance of “balance” may be a theatrical contrivance distracting attention from important wrongs. Passionate commitment to social justice, while open to political manipulation, may sometimes provides the necessary energy and persistence to secure fairer, truer coverage, than the Anglo-American model. The study confirms the hypothesis that the Honduran crisis evoked different responses from different international 24/7 television news channels and that these differences mapped on to the political orientation of their respective governments, and of inequalities of power and tensions between these governments. We believe the study vindicates our choice of the terms hegemon, subaltern and counter-hegemon to articulate such inequalities and tensions.

Finally, we should note the limitations of this study. The Honduran crisis spanned several months, and continues to simmer at the time of writing, while this analysis looked at just a few days of news coverage. Further study of newscasts during the subsequent weeks and months would enable a more definitive conclusion.

1.Despite this initial condemnation by the United States, the country has been criticized for not doing enough to show demonstrate its opposition to the coup, including stopping short of actually calling what happened a “coup”. (See Mr. Arias Steps In; New York Times (Editorial); July 9, 2009)

2. This accounted for the entire newscast. It is worth noting that during the breaks TeleSur broadcast promotional excepts of its Honduras coverage. In effect virtually the entire hour, including breaks, was dedicated to the crisis.

3. TeleSur does very briefly allude to pro-Micheletti protests in San Pedro Sula but it does not show images of these protests.

4. This according to TeleSur. We could not find confirmation of the protests elsewhere.

5. An article by EFE backs up these reports: Activistas hondurenos denuncian reclutamiento forzado y amenazas, EFE, July 1st 2009

6. Articles by the New York Times (Lacey and Thompson, July 1st 2009) and the Chinese Xinhua news agency (Xinhua, June 30th 2009) mention this grenade attack. They say the incident was reported by the coup government.

7. Inter-American Commission on Human Rights; Preliminary Observation on the IACHR visit to Honduras, August 21, 2009; http://www.cidh.org/Comunicados/English/2009/60-09eng.Preliminary.Observations.htm

8. Both channels were quick to denounce repression and censorship by the Iranian government after the election crisis there. They also broadcast videos allegedly posted by Iranians on Youtube – hardly a reliable source of information.

9. It is possible that CNN and NTN24 did make more of the alleged repression and censorship during other newscasts. CNN itself suffered from censorship by the coup regime on the first day of the crisis after its signal was cut. Even so, the fact that these issues were brushed over during this three-day period of intense activity in Honduras sounds alarm bells.

10. To give just one example: Unos 5 mil foráneos ‘melistas’ hay aquí, La Prensa, Honduras; July 9, 2009

11. To its credit, NTN24 did broadcast an exclusive interview with Zelaya’s wife Xiomara Castro de Zelaya in which she provided details of her family’s ordeal as a result of the coup against her husband.

Claudia Boyd-Barrett is a freelance newspaper and radio reporter with a keen interest in Latin America. She lived in Mexico City for four years where she worked for the U.S-based human rights organization Global Exchange, the English-language paper The News and for the Miami Herald's International Edition. In 2007 she received a fellowship from the Inter American Press Association to study for a Masters degree in journalism at the Universidad de San Andrés in Buenos Aires, Argentina. She spent a year in Buenos Aires taking classes at the headquarters of the country's main newspaper "Clarin", and interned for the 24-hour news channel Todo Noticias. Claudia is fluent in Spanish and currently resides in the U.S. where she is completing her Masters thesis on Latin American news stations. Contact: cboydbarrett@gmail.com

Oliver Boyd-Barrett is Professor of Journalism at Bowling Green State University, Ohio. He has held previous positions at California State University, Leicester University and the Open University. He has published extensively on issues related to international news flow and the role of both national and international news agencies in the maintenance of a global news system. His books include The international news agencies (1980), Contra-flow in global news (1992)(with Daya Thussu), The globalization of news (1998)(co-editor with Tehri Rantanen), Communications media, globalization and empire (2006)(editor), News agencies in the turbulent era of the Internet (forthcoming). Contact: oboydb@bgsu.edu

Copyright © 2026 Global Media Journal, All Rights Reserved